In 1877, a stained-glass window depicted Jesus as Black for the first time − a scholar of visual images unpacks its history and significance.

By Virginia Raguin, The Conversation

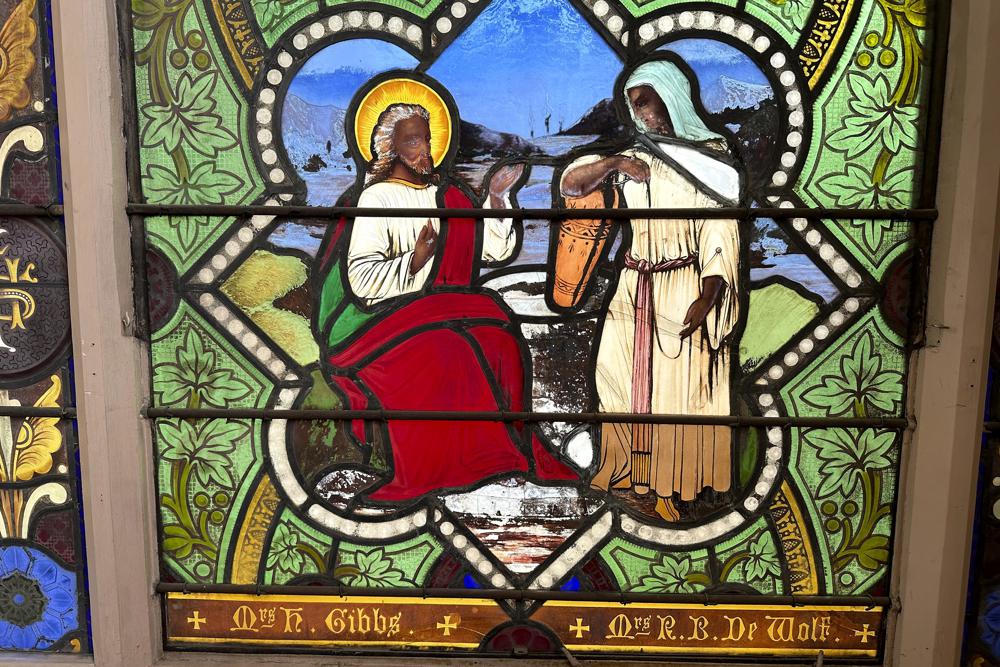

A stained-glass window, donated in 1877 to a church in Rhode Island, shows Jesus as a dark-skinned man. Western depictions portrayed him as a European, with light skin and sometimes even with blue eyes. A Black Jesus at this time was unknown.

Now in the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, the window was made by the studio of Henry Sharp, a prominent 19th-century American stained-glassmaker who was popular with Episcopal congregations. Sharp’s first three windows for the now-closed St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Warren, Rhode Island, were of solitary white male figures, including one of Christ as “Salvator Mundi,” or Savior of the World. Christ is rigid, staring fixedly and holding an orb, a symbol of worldly power.

The Black Jesus window is different – instead of depicting a singular saintly figure, the 12-by-5-foot window tells a full narrative. It depicts scenes of Jesus speaking with women who also have dark brown skin.

As a scholar of images, I believe that the window speaks about equality, not only of race, but of gender, class, and ethnicity.

The scenes were based on two Bibles published in the 1860s, illustrated by the German artist Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld and the French artist Gustave Dore. Von Carolsfeld provided the model for the first scene, when Jesus visits his friends for dinner – two sisters named Mary and Martha and their brother Lazarus.

In the Gospel of Luke, Christ criticizes Martha for being preoccupied with preparation for receiving guests and praises Mary, sitting immobile at his feet so that she can listen. In the window, however, service and contemplation are equally praised. Christ looks directly at Martha standing and Mary sitting. Like the medieval monastic model of “ora et labora,” or prayer and labor – both seen as complementary elements of society.

In a second image on the same window, Christ speaks with a Samaritan woman alone, which, during that time, men were not supposed to do. Additionally, the Samaritans, an ethnic group living in the Middle East, were viewed at the time by the Jews as different and inferior. Christ, however, asks her for water and tells her that he is Son of God, the Messiah.

I, along with other conservators who have examined the window, found the dark paint used for the skin color authentic and not a result of any deterioration, which can have a darkening effect on paintings over time. This color skin, as far as art historians know, was not used in any other window before this time.

The donor, a woman named Mary P. Carr, honored the memory of two women whom she named in the inscription. One, Ruth Bourne DeWolf, had married John DeWolf, a descendant of the Bristol family that had built its great fortune through transport of enslaved Africans. She and Hannah Gibbs, the other woman named, gave money to the American Colonization Society that supported the passage of free Africans to Africa.

Carr’s commission dates to the same year of the U.S. Congress’ Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended post-Civil War Reconstruction. I argue that this was not a coincidence, but that Carr intended the window as a protest against the segregation laws being enacted that led to the era of “Jim Crow” in Southern states. She also wanted to seek more respect for women’s work.

The window not only depicts women at work but shows Jesus directly talking respectfully to these women as they are working.

Virginia Raguin is Distinguished Professor of Humanities Emerita, Visual Arts, College of the Holy Cross.

First published April 5, 2024