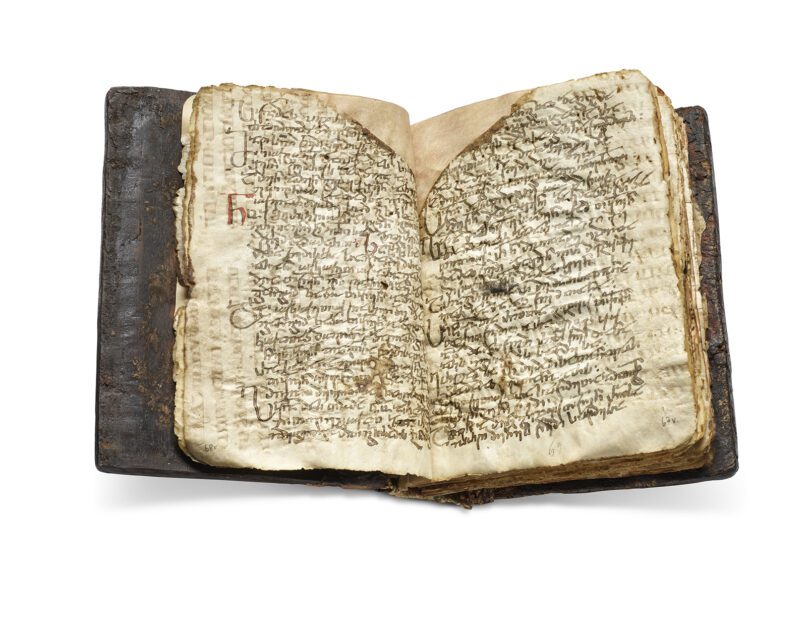

The starring role in a June auction at Christie’s will be taken by the Crosby-Schoyen Codex, the oldest known book in private hands. Written on papyrus in the Coptic language, it contains the oldest complete version of the First Epistle of Peter and the Book of Jonah.

By Catherine Pepinster

LONDON (RNS) — Amid all the preparations to turn Paris into a venue for the Olympic Games that begin in less than 100 days, one small corner of the French capital is preparing for another modern form of competition based in antiquity: Christie’s auction of early Christian texts from North Africa.

Some of the most important religious artifacts to come up for sale in recent years, the manuscripts from the privately owned Schoyen Collection, including the oldest complete version of the First Epistle of Peter and the Book of Jonah, were displayed in New York earlier this month and have arrived in Paris for inspection by prospective bidders. The auction sale of the works, written on papyrus in the Coptic language, will take place at Christie’s in London in June.

The viewings of the Schoyen Collection have drawn representatives from museums around the world as well as private collectors. To some they represent beauty, to others links to the past, and to others a connection with faith.

“This is one of the most important sales Christie’s has ever held in this field,” said Eugenio Donadoni, senior specialist in medieval and Renaissance manuscripts at Christie’s. “They are touchstones, helping us understand the history of Christianity.”

The Schoyen Collection is the work of Martin Schoyen, building on the collections of his father, and now comprises 20,000 manuscripts, including 400 linked to the Bible. Now in his 80s, Schoyen has decided to sell part of it, including the most important artifacts.

According to Donadoni, the Crosby-Schoyen Codex — valued at £3 million or about $3.7 million — is thought to be the world’s oldest book in private hands, comprising, besides Peter’s epistle and the story of Jonah, part of the Book of Maccabees and an Easter homily. It is highly significant in the history of writing, said Donadoni, because it “marks a pivotal moment — it is the transition from scrolls to codicils as Christianity spreads across the Mediterranean.”

But the codex also shows the religious pivot going on at the time. It is thought that the codex was used by a monastery in upper Egypt around the middle of the third century CE, before the Council of Nicaea in 325, which tried to secure consensus on issues of Christian belief, such as the relationship between God the Father and God the Son, and the latter’s divine nature.

“You can see from the codex that they are finding their feet as Christians,” said Donadoni. “They are still steeped in Jewish tradition and are shaping the new religion.”

The book is so old that it calls the text now known as the First Epistle of Peter the letter of Peter, as if they are not aware that a further letter exists.

Another major manuscript going up for sale on June 11 is the Codex Sinaiticus Rescriptus, which is in effect an ancient effort at recycling. In the 10th century, John Zosimos, a monk at a monastery near Jerusalem, acquired a document written on expensive vellum, which he packed up and took to St. Catherine’s monastery in the Sinai Desert to reuse for his own writing. The original writing, itself the earliest surviving piece of the Gospels to be written in Aramaic, dating from the fifth or sixth century, is still visible.

“The underlying text was not scrubbed out very well, so under fluorescent lighting you can still see it, written in the language that Jesus himself would have spoken,” said Donadoni.

The document, valued at £1.5 million, or $1.85 million, is a bargain, as the buyer gets the two texts for the price of one.

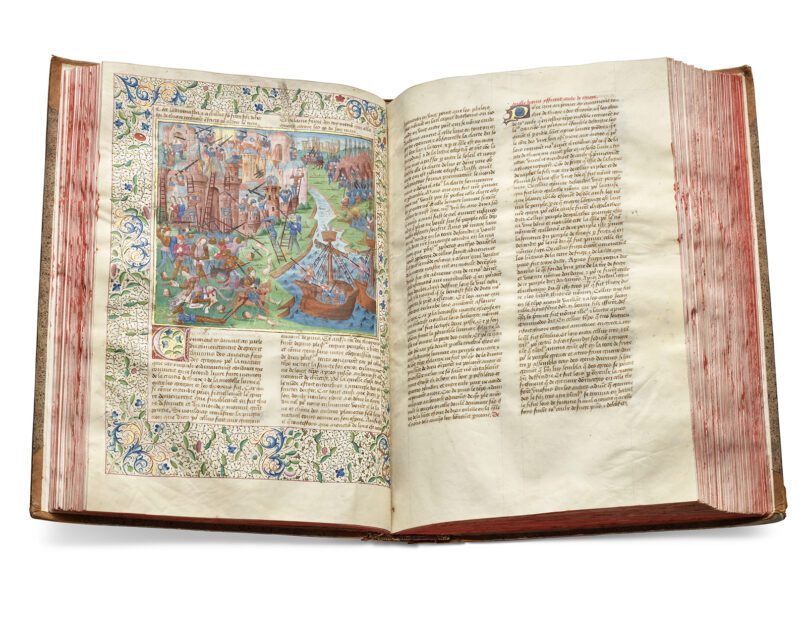

Also, part of the Schoyen Collection is the Holkham Hebrew Bible, a Sephardic manuscript in Hebrew from the 13th century, the Geraardsbergen Bible from late 12th-century Flanders, and a commentary on the Gospels by the Venerable Bede from the 11th century.

Last year the Codex Sassoon, a Hebrew Bible more than 1,000 years old, became the most valuable manuscript sold at auction when it went for $38.1 million at Sotheby’s in New York, confirming New York as the leading market for Hebraic religious texts, while London remains the capital for sales of illuminated Christian texts. But both centers attract buyers, including museums, from around the world.

Prices are believed to have been pushed higher by the intervention of one major player: the Green family, U.S. evangelical Christians who have used their fortune created by the Hobby Lobby chain of craft stores to purchase illuminated, or decorated, manuscripts, Torahs, papyri and other works worth $20 million to $40 million from auction houses, dealers, private collectors and institutions. Items from the Green collection were donated to the Museum of the Bible in Washington, a family project that opened in 2017 with a mission to “inspire confidence in the absolute authority and reliability of the Bible.” It has since stepped back from this evangelical purpose and says that it is an “institution whose purpose is to invite all people to engage with the transformative power of the Bible.”

Meanwhile, the Faith and Liberty Discovery Center, a Bible museum created by the American Bible Society in Philadelphia, announced that it will shut its doors after fewer than three years of operation and an investment of $60 million. Opened in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, it failed to draw anywhere close to its projected 250,000 annual visitors.

The British and Foreign Bible Society, which has the biggest collection of Bibles and other religious books and documents in the world, has shied away from opening a museum, although it does open its collection, based at Cambridge University, to scholars and researchers. While it still expands through legacies and donations and is committed to good stewardship of its existing treasures, the BFBS does not acquire items with its own funds, preferring, it says, to disseminate the Bible and be involved in mission rather than convey the message that the Bible is a museum piece.

In recent times there have been concerns that some items held by Biblical manuscript collectors have been acquired through the black market, especially from people in trouble spots in the Middle East. According to Christie’s Donadoni, all the items from the Schoyen Collection that are up for auction in June have had their provenance vetted and have been checked extensively by its legal department.

First published April 22, 2024