‘Is the Black church dead? I think it really varies depending on which traditions we’re talking about,’ said Shelton, a sociologist at the University of Texas at Arlington.

By Adelle M. Banks

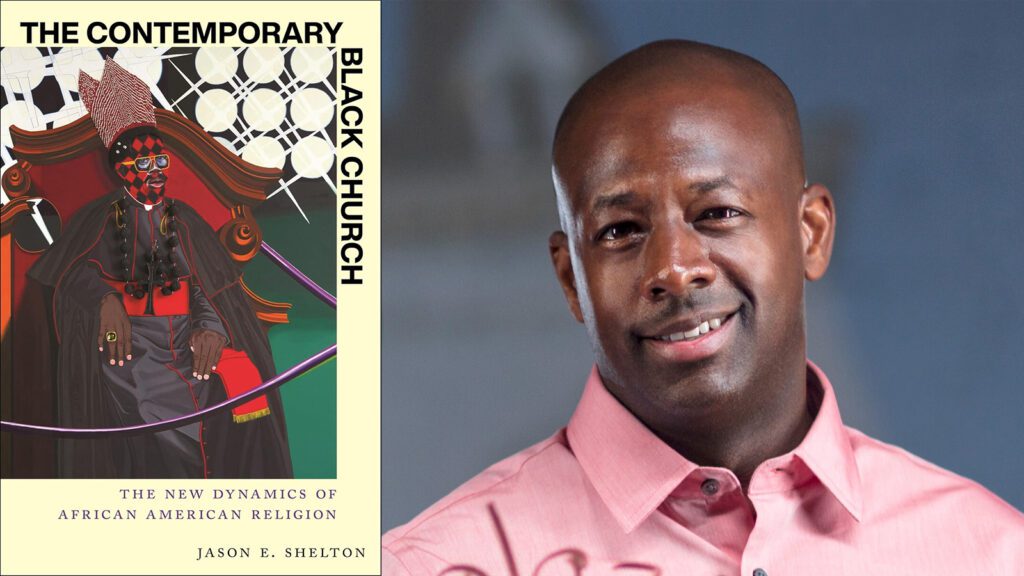

(RNS) — Jason Shelton has made a deep scholarly dive into the world of the Black church.

But not everything in his new book, “The Contemporary Black Church: The New Dynamics of African American Religion,” was learned at the University of Texas at Arlington, where Shelton is a sociologist. He drew as well from his experience growing up in Black churches, in his familial home in Ohio and in Los Angeles — at United Methodist, Church of God in Christ, African Methodist Episcopal and nondenominational churches — and searching as an adult for the right spiritual space for his family.

“It was important to me to find a thriving Black Methodist congregation that I could raise my daughters in, and my wife and I had a difficult time,” he said in a recent interview. “Here we are in (the Dallas-Fort Worth area), and it’s hard to find a young congregation that’s thriving, where I feel like my daughters can develop their own memories and find bonds with other kids, and we can be with other young families. And so that really made me realize there’s a story here to be told about religion in Black America.”

Shelton, 48, and a colleague developed what he calls “Black RelTrad,” a coding scheme that allowed him to delve into the beliefs and practices of a range of Black believers, including Protestants, Catholics and non-Christians, and nonbelievers.

Shelton, who also is the director of UTA’s Center for African American Studies, talked with RNS about religious differences in Black America, the effects of “disestablishment” on Black churches and whether the “spiritual but not religious” can be reclaimed by them.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

You open your book recalling your connections with churches from different expressions of the Black church and leaders such as the Rev. James Lawson and Bishop Charles Blake. How did that experience shape you?

Those early years were definitely formative, in that they left me with impressions about various ways that African Americans express faith. When I got to Ohio, I was able to compare St. James (AME Church in Cleveland) to Holman United Methodist Church, and then compare them to the nondenominational church that my parents were attending in Cleveland, and then compare that to West Angeles (Church of God in Christ).

They all left these distinct impressions about variation and diversity. Decades later, I would look back and say, oh my gosh, modern-day researchers have clearly lumped Black folks together like we’re this monolithic group, and I just knew in my own walk in life that was not the case.

For years, experts such as Eddie Glaude have asked if the Black church is dead. As you look at the numbers, do you agree or disagree?

I wouldn’t say that it is dead, but certain denominations are in a lot of trouble — that Black Methodist tradition I’ve called home is in a lot of trouble. I’d say the Baptists are also a tradition that has to look and see some trouble down the road. On the flip side, I would say the Holiness Pentecostal tradition in Black America has always been small, but it’s held its ground over the decades. The Black Catholic tradition, always been small, but held its ground. So is the Black church dead? It really depends on which traditions we’re talking about.

What do you see as the main difference between the mainline African American Protestants and the evangelical African American Protestants?

These are Black folks who are believers, and on a Sunday, how they think about, practice their faith, oftentimes are still very similar in orientation. That being said, (some) Black Methodists seem to be a lot more open on LGBT issues, whereas we know the AME (African Methodist Episcopal) is very clear, uh-uh, that’s not a line clergy are ready to cross. The four traditions in today’s world that comprise the heart of the contemporary Black church are the Baptists, the Methodists, the Holiness Pentecostals and the nondenoms. Of the four of those, the nondenoms are more likely to vote for a Republican presidential candidate. That’s a big break from what we’ve seen in the past.

You describe the “Third Disestablishment in Black America.” What does it mean for the Black church?

You’re seeing these young people, particularly millennials, moving away from organized religion in very strong numbers. The baby boomers held on. It started with my generation in the late 1990s, those Gen Xers. But now with the millennials, it’s moving and taking big jumps forward in terms of the number of African Americans who are not affiliating with organized religion.

You mention the changing levels of education of the Black clergyperson and the Black churchgoers. What’s happened there? What’s at stake?

The idea was that the Black preacher was the leader of the community for most of Black history. In light of all that racism and segregation, the pastor was typically the most educated person in the community because that person could stand up and read the Bible and interpret the Bible and speak to the masses in that congregation. Fast-forward the clock: African Americans in church are oftentimes more educated than the senior pastor in the pulpit. In this modern, technological, mainstream American society, you can sit in church and question what the pastor’s saying in real time.

I argue that a consequence of the success of the Civil Rights Movement is that the church has become voluntary. There was the time that we were expected to be at church. Of course, it’s holding in particular families, don’t get me wrong. But overall, as more and more Black folks have made it to the middle class, and as more and more of us have more options on Sundays, it has undermined organized religion in Black America, and education is the driving force.

You say, though, that there are strong reasons to believe that some of the SBNR — spiritual but not religious — can be reclaimed.

A great number of these SBNRs still believe in God. A great number of these SBNRs still go to church, and some go to church more than once a month. Those are the folks that can be maybe more easily reclaimed, as compared to the person who has completely moved away from organized religion and just says, “Oh no, I don’t believe those beliefs about God,” or “I don’t believe those things about Christ.”

But there’s got to be some kind of reckoning and some kind of reconciliation to bring those folks back in.

You cited hopes of Christians you interviewed for changes that could help draw more young people back to church. Can you give an example? Are you aware of churches that are succeeding?

One of them was to remove status barriers within the church, the classic idea that a pastor wears the robe. Less formality was one of those things. Another one of those things, which a lot of people emphasized, was giving leadership opportunities to 30-somethings.

I can tell you, in my own personal life, part of the reason that we picked the church we did is that a lot of those things are happening. We don’t call our pastor “Reverend,” we call him Derek. There are a lot of young people in leadership. Grandmama is on the usher board too, but there are a lot of younger people that are engaged and a part of it as well. Those are the kinds of things that, particularly, folks have found welcoming.

What worries you most about the state of the contemporary Black church?

Who speaks for the poor? The Black church has spoken for the poor. As the church declines, we’re not only losing the most important institutional anchor we’ve had, we’re also losing an important political and social institution that helped to try to force America to say “Here’s the counterpoint to everything is fine and great. No. Look over here. There’s more work to be done.”

But your postscript starts with the words “Be optimistic!” Why?

Regardless of what people’s faith is, and how they affiliate, and what they may say or may not say about a particular faith, for a great number of us, there’s still a sense that there are problems that need to be addressed for us as African Americans. There’s a commonality that connects us as African Americans, at least for our generation. Who knows what it is in the future? But that is something, I think, to be optimistic about.

First published Sept. 3, 2024