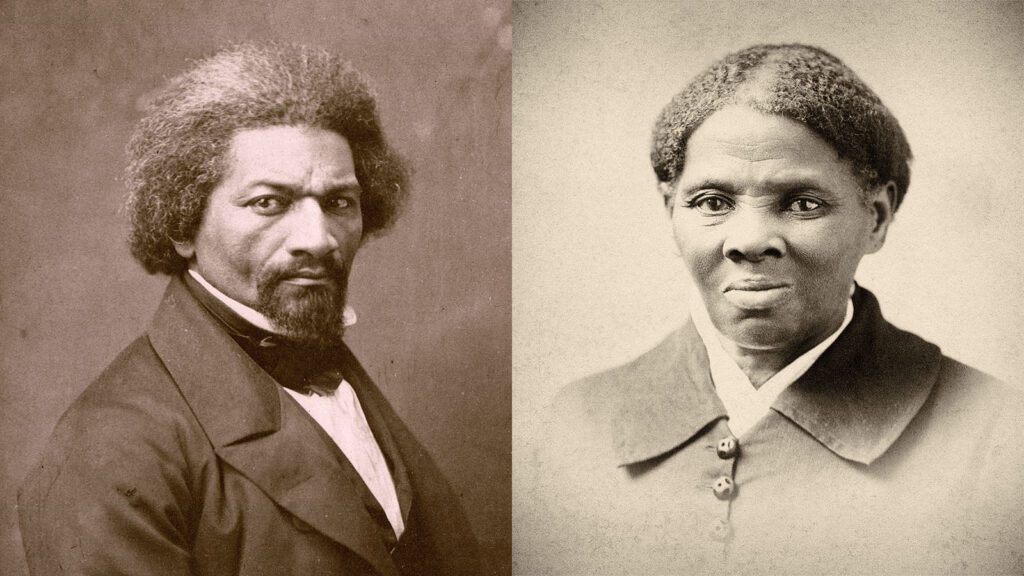

‘Religion for both Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass was the foundation in many ways of who they are,’ said co-director Stanley Nelson.

By Adelle M. Banks

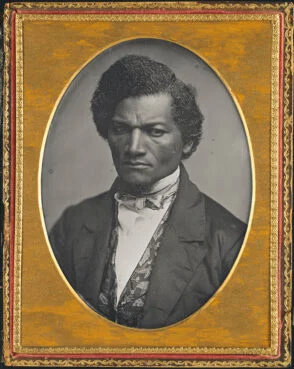

(RNS) — Frederick Douglass called the Bible one of his most important resources and was involved in Black church circles as he spent his life working to end what he called the “peculiar institution” of slavery.

Harriet Tubman sensed divine inspiration amid her actions to free herself and dozens of others who had been enslaved in the American South.

The two abolitionists are subjects of a twin set of documentaries, “Becoming Frederick Douglass” and “Harriet Tubman: Visions of Freedom,” co-productions of Maryland Public Television and Firelight Films and released by PBS this month (October).

“I think that the faith journey of both Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass were a huge part of their story,” Stanley Nelson, co-director with Nicole London of the two hourlong films, said in an interview with Religion News Service.

“Religion for both Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass was the foundation in many ways of who they are,” Nelson added.

The films, whose production took more than three years in part due to a COVID-19 hiatus, detail the horrors of slavery both Tubman and Douglass witnessed. Tubman saw her sister being sold to a new enslaver and torn away from her children. A young Douglass hid in a closet as he watched his aunt being beaten. They each expressed beliefs in the providence of God playing a role in the gaining of their freedom.

Scholars in both films spoke of the faith of these “original abolitionists,” as University of Connecticut historian Manisha Sinha called people like Tubman, who took to pulpits and lecterns as they strove to end the ownership of members of their race and sought to convince white people to join their cause.

“The Bible was foundational to Douglass as a writer, orator, and activist,” Harvard University scholar John Stauffer told Religion News Service in an email, expanding on his comments in the film about the onetime lay preacher. “It influenced him probably more than any other single work.”

Stauffer said the holy book, which shaped Douglass’ talks and writings, was the subject of lessons at a Sunday school he organized to teach other slaves.

“It’s impossible to appreciate or understand Douglass without recognizing the enormous influence the Bible had on him and his extraordinary knowledge of it,” Stauffer added.

Actor Wendell Pierce provides the voice of Douglass in the films, quoting him saying in an autobiography that William Lloyd Garrison’s weekly abolitionist newspaper The Liberator “took a place in my heart second only to the Bible.”

The documentary notes that Douglass was part of Baltimore’s African Methodist Episcopal Church circles that included many free Black people. Scholars say he met his future wife Anna Murray, who encouraged him to pursue his own freedom, in that city.

“The AME Church was central in not only creating a space for African Americans to worship but creating a network of support for African Americans who were committed to anti-slavery,” said Georgetown University historian Marcia Chatelain, in the film.

The Douglass documentary premiered Tuesday, Oct. 11, on PBS. It and the Tubman documentary, which first aired Oct. 4, will be available to stream for free for 30 days on PBS.org and the PBS video app after their initial air dates. After streaming on PBS’ website and other locations for a month, the films, which include footage from Maryland’s Eastern Shore where both Douglass and Tubman were born, will then be available on PBS Passport.

The Tubman documentary opens with her words, spoken by actress Alfre Woodard.

“God’s time is always near,” she says, in words she told writer Ednah Dow Littlehale Cheney around 1850. “He set the North Star in the heavens. He gave me the strength in my limbs. He meant I should be free.”

Tubman, who early in life sustained a serious injury and experienced subsequent seizures and serious headaches, often had visions she interpreted as “signposts from God,” said Rutgers University historian Erica A. Dunbar in the film.

The woman known as “Moses” freed slaves by leading them through nighttime escapes and later as a scout for the Union Army in the Civil War.

“She never accepted praise or responsibility, even, for these great feats,” Dunbar said. “She always saw herself as a vessel of her God.”

But, nevertheless, praise for Tubman came from Douglass, who noted in an 1868 letter to her that while his work was often public, hers was primarily in secret, recognized only by the “heartfelt, ‘God bless you’” from people she had helped reach freedom.

Nelson, a religiously unaffiliated man who created films about the mission work of the United Methodist Church early in his career, said the documentary helps shed light on the importance faith held for Tubman.

“It’s something that most people don’t know and so many people who see the film for the first time are kind of surprised at that,” he said in an interview. “She felt she was guided by a divine spirit and the spirit told her what to do.”

First published Oct. 11, 2022