BY SARA CLINE in Baton Rouge, LA, and Kevin McGill in New Orleans

The Associated Press — Gov. Jeff Landry has signed into law legislation that makes Louisiana the first state to require that the Ten Commandments be displayed in every public school and at colleges.

The Republican-dominated legislature is pushing to expand religion into day-to-day life.

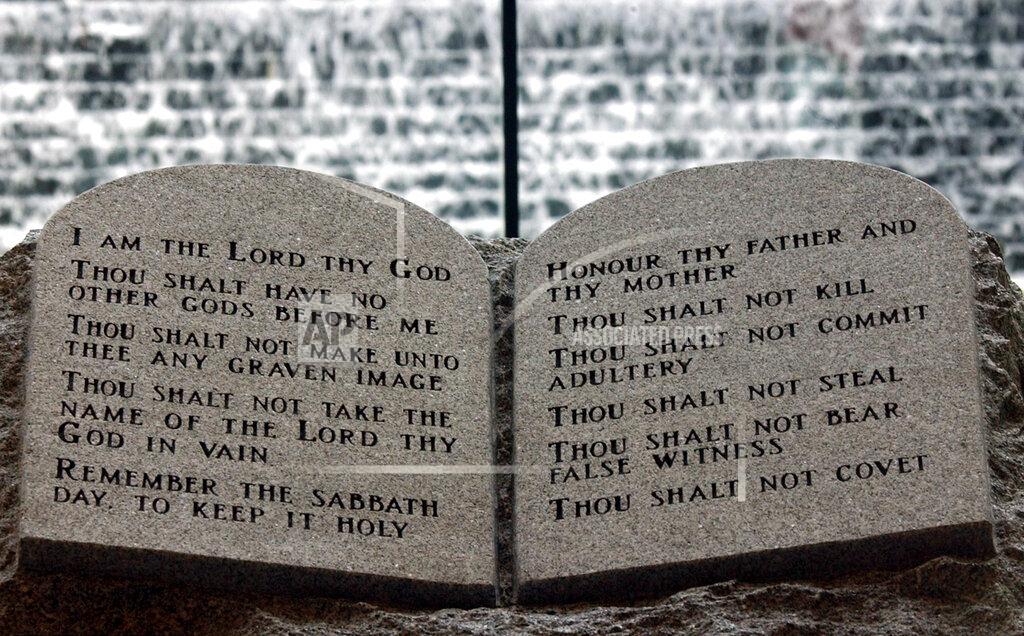

Under the new law, all public K-12 classrooms and state-funded universities will be required to post a poster-sized display of the Ten Commandments in “large, easily readable font” next year.

Civil liberties groups planned lawsuits to block the law, saying it would unconstitutionally breach protections against government-imposed religion.

Chris Dier, who was named the Louisiana Teacher of the Year in 2020, said Thursday (6/20/24) that he worried the required display could send a message that a “teacher, school, community and state prefers certain religions over others” and could make some students “feel incredibly isolated.”

State officials are stressing the history of the Ten Commandments, which the bill calls “foundational documents of our state and national government.”

“The 10 Commandments are pretty simple (don’t kill, steal, cheat on your wife), but they also are important to our country’s foundations,” Attorney Gen. Liz Murrill, a Republican ally of Landry who will defend the law in court, said in a social media statement.

The GOP-authored bill comes during a new era of conservative leadership in Louisiana under Landry, who succeeded two-term Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards in January. The state’s reliably red Legislature also has a GOP super majority, and Republicans hold every statewide elected position, paving the way for lawmakers to push a conservative agenda. That includes a package of anti-LGBTQ+ bills, tough-on-crime policies, migrant enforcement measures and legislation mirroring conservative plans in Texas and Florida.

Similar bills requiring the Ten Commandments be displayed in classrooms have been proposed in other statehouses — including Texas, Oklahoma, and Utah.

However, with threats of legal battles over the constitutionality of such measures, no state had succeeded in the bills becoming law until Louisiana. Legal battles over the Ten Commandments in classrooms are not new.

In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a similar Kentucky law was unconstitutional and in violation of the establishment clause of the U.S. Constitution, which says Congress can “make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” The high court found that the law had no secular purpose, but rather served a plainly religious purpose.

In its most recent rulings on Ten Commandments displays, the Supreme Court held in 2005 that such displays in a pair of Kentucky courthouses violated the Constitution. At the same time, the court upheld a Ten Commandments marker on the grounds of the Texas state Capitol in Austin. Those were 5-4 decisions, but the court’s makeup has changed, with a 6-3 conservative majority now.

In Louisiana, a state ensconced in the Bible Belt, proponents of the bill argue that the measure is constitutional on historical grounds.

GOP state Sen. Jay Morris recently said that “the purpose is not solely religious to have the Ten Commandments displayed in our schools, but rather its historical significance.” He went on to say that the Ten Commandments is “simply one of many documents that display the history of our country and the foundation for our legal system.”

The law also “authorizes” — but does not require — the display of the Mayflower Compact, the Declaration of Independence and the Northwest Ordinance in K-12 public schools.

Opponents continue to question the bill’s constitutionality.

Democratic state Sen. Royce Duplessis argued that while supporters of the legislation say the intent of the bill is for historical significance, it does not give the state “constitutional cover” and has serious problems. The lawmaker questioned why the Legislature was focusing on the display of the Ten Commandments, saying there are many more “documents that are historical in nature.”

“I was raised Catholic, and I still am a practicing Catholic, but I didn’t have to learn the Ten Commandments in school,” Duplessis said recently. “It is why we have church. If you want your kids to learn about the Ten Commandments take them to church.”

The author of the bill, GOP state Rep. Dodie Horton, argued earlier this session that the Ten Commandments do not solely have to do with one religion.

“This is not preaching a Christian religion. It’s not preaching any religion. It’s teaching a moral code,” Horton said during a committee hearing in April. Last year, the lawmaker sponsored another law that requires all schools to display the national motto “In God We Trust″ in public classrooms.

Some opponents noted that while schools may soon be required to display the Ten Commandments, the Legislature also has recently passed a bill that broadly bars teachers from discussing gender identity and sexual orientation in public school classrooms.

And while lawmakers are debating what can and can’t be discussed in school and what should be displayed, some say there are more pressing education issues plaguing the state.

“We really need to be teaching our kids how to become literate, to be able to actually read the Ten Commandments that we’re talking about posting. I think that should be the focus and not this big what I would consider a divisive bill.” Duplessis said.

Louisiana routinely reports poor national education rankings. According to the State Department of Education in the fall of 2022 only half of K-3 students in the state were reading at their grade level.

How the Ten Commandments are viewed.

Jews and Christians regard the Ten Commandments as having been given by God to Moses, according to biblical accounts, on Mount Sinai. Not every Christian tradition uses the same Ten Commandments. The order varies as does the phrasing, depending on which Bible translation is used. The Ten Commandments in the signed Louisiana legislation are listed in an order common among some Protestant and Orthodox traditions.

First published June 20, 2024