By Laura Meckler, The Washington Post

The Oklahoma Supreme Court considered Tuesday whether the state can directly fund religious education, with some justices voicing skepticism that aproposed Catholic charter school could pass constitutional muster but others suggesting there may be little difference betweensuch a schooland other instances of tax dollars supporting religious entities.

At issue was a proposal to create an overtly religious online charter school, the first of its kind in the country. But people on both sides of the closely watched case have said its ramifications could stretch well beyond the state and couldprovide the U.S. Supreme Court an opportunity to expand on recent rulings widening the use of tax dollars in support of religious education.

“Are we being used as a test case? It sure looks like it,” said Justice Yvonne Kauger,who suggested that a complete dismantling of the wall between church and state would have far-reaching consequences. “When the wall comes down, it’s ‘Katy, bar the door.’ Everyone would be affected.”

Last year, the Oklahoma Statewide Virtual Charter School Board voted 3-2 to approve St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, to be operated by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the Diocese of Tulsa. School leaders said it would approach religion the same way private Catholic schools do, with teachings woven into every subject from math and science to history and literature. The school also plans to consider religion in hiring; the principal, for instance, must be Catholic.

Charter schools are publicly funded but privately run and must abide by many of the rules that govern traditional public schools.

Oklahoma law clearly states that charter schools may not be sectarian or affiliated with a religious institution, and the state constitution bars spending public money, directly or indirectly, for any religious purpose, including teaching. Voters rejected an effort in 2016 to change the state’s constitution, with 57 percent voting no to allowing such spending.

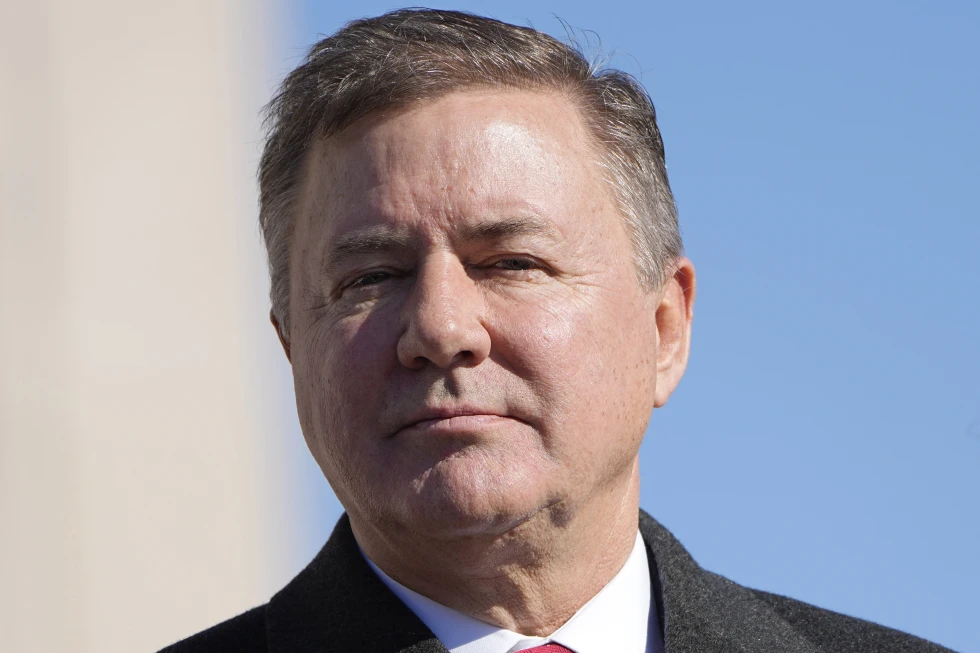

Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond (R) sued the virtual charter board last year after it approved the St. Isidore application and argued the case against the school on Tuesday. He told the courtthat the proposed school is a blatant violation of both the state and federal constitutions and allowing it could have “unlimited” unintended consequences.

“If this charter school is authorized by this court, then the state of Oklahoma effectively has control over the school. That’s the state controlling religion,” Drummond said.“That is a slope for which there is no end.”

He suggested that supporters’ objective was “to come into this red state and push us to the limit” and push the constitutional question.

The U.S. Supreme Court has said that government cannot exclude religious entities from otherwise available public programs, including taxpayer-funded voucher programs for private schools, which many states including Oklahoma offer.

Justice Dana Kuehn questioned how the state can justify funding vouchers, given the constitutional prohibition toward funding religion, but say no to a religious charter school.

Drummond replied that in the case of vouchers, the money is given to the parents, who then choose a private school. A charter school is different, Drummond said, because it is created and funded by the state itself. He had warned the state charter school board that approving the St. Isidore application would be unconstitutional. After the board went ahead anyway, Drummond filed suit to stop it, saying members of the charter school board had intentionally violated their oath of office.

Another suit, this one filed by a group of parents, clergy and education activists, is also challenging the new school’s approval.

Supporters of the school say rulings from the U.S. Supreme Court bolster the charter board’s approval and noted that the state’s previous attorney general had blessed the plan. Phil Sechler, senior counsel with the advocacy group Alliance Defending Freedom, who represented the state charter school board, said the Constitution’s guarantee of free exercise of religion means the government cannot discriminate against a religious school simply because it is religious.

“Much is at stake in this case,” he said, including “religious liberty itself.”

In recent years, religious activists have succeeded in tearing down what had been a clear delineation between public funding and religious education. In three significant rulings, the U.S. Supreme Court found that religious institutions may not be excluded from taxpayer-funded programs that were available to others.

In a 2017 case, the high court ruled that a church-run preschool in Missouri was entitled to a state grant that funded playgrounds. In 2020, the court ruled that Montana could include religious schools in a program giving tax incentives for supporting private-school tuition scholarships. And last year, the court said that a Maine voucher program that sent rural students to private high schools had to be open to religious schools.

Among the questions argued Tuesday was whether the proposed virtual school, in receiving state funding, would be a “state actor” required to follow rules governing government conduct. The school’s supporters argued it would be more like a religious hospital that receives funding from the government for services provided.

“When the state is contracting with a private religious entity, it’s not providing a gratuitous benefit or supporting that sectarian institution. It’s receiving a service and providing money in return,” said Michael McGinley, the attorney representing the school.

Drummond countered that St. Isidore became a public school subject to public rules the moment it signed the contract to become a charter school.

“With the charter in place, it is a public entity,” he said.

Kuehn suggested another line of argument: that public schools may be practicing a form of religion if teachers talk about subjects in a way that runs counter to certain religious beliefs.

“If a public school … decides to teach against religion, against certain biblical thought — whether it’s from evolution to gender or whatnot — do you believe that that’s a public school taking on a stance about religion itself?” she asked.

If this is acceptable, the question suggested, why would it be unconstitutional to fund a school taking the opposite stance?

Leaders of the proposed school have said they created it in part to provide Catholic education for students in rural areas that do not have a private Catholic school nearby. But it also was set up to test the legal limits of taxpayer funding for religious schools, part of a conservative push to expand the boundaries of school choice.

The school’s supporters include Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt (R) and many others in the school choice movement who are rooting for its success as a way to offer parents more options. While many states offer vouchers that can be used for religious schools, the vouchers do not always cover the full tuition; charter school costs are covered entirely with tax dollars.

Although this case was filed in state court, many expect it will ultimately be decided by the U.S. Supreme Court.

“It seems almost like something on the fringe, a minor case somewhere out in Oklahoma. Actually, I think a lot rides on the outcome of the case,” said Charles Haynes, founder of the Freedom Forum’s Religious Freedom Center and one of the country’s top experts on religion in schools.

If the Oklahoma school prevails, he said, “does this mean then that religions can now start charter schools and they can be religious in nature and they can get the same funding as public schools?”

“If that’s what it means,” he said, “it’s a huge change.”

First published April 2, 2024